- Home

- Philip Weinstein

B006JHRY9S EBOK

B006JHRY9S EBOK Read online

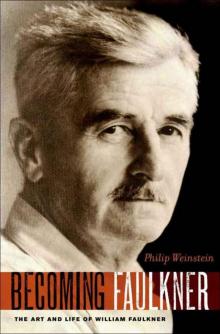

BECOMING FAULKNER

BECOMING FAULKNER

The Art and Life of William Faulkner

PHILIP WEINSTEIN

Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further

Oxford University’s objective of excellence

in research, scholarship, and education.

OXFORD NEW YORK

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

WITH OFFICES IN

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Copyright © 2010 by Philip Weinstein

Published by Oxford University Press, Inc.

198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016

www.oup.com

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Weinstein, Philip M.

Becoming Faulkner : the art and life of William Faulkner / Philip Weinstein.

p. cm

ISBN 978-0-19-534153-9

1. Faulkner, William, 1897-1962. 2. Novelists, American—20th

century—Biography. 1. Title.

PS3511.A86Z98548 2009

813’.52—dc22 2009013181

[B]

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

Table of Contents

Abbreviations

PROLOGUE “Cant Matter”

CHAPTER ONE Crisis and Childhood

CHAPTER TWO Untimely

CHAPTER THREE Dark Twins

CHAPTER FOUR In Search of Sanctuary

CHAPTER FIVE Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow

EPILOGUE “Must Matter”

Notes

Index

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

All of one’s book are indebted to others beyond the power to acknowledge, but this one benefits from an indebtedness both more obvious and more profound.

Some seven years ago I received a telephone call from Alice Tasman, of the Jean V. Naggar Literary Agency in New York. As an undergraduate (years earlier), she had studied Faulkner with my brother Arnold, at Brown University. An agent now, she wanted to coax into being a biographical study of Faulkner that would do justice to the impact his work had had on her. I responded that I was at that time immersed in writing a larger study of modernism (Unknowing: The Work of Modernist Fiction), and that I was—however invested professionally in Faulkner’s work—no biographer. During the next four years, three events occurred that changed my mind. I finished writing Unknowing, and I read in draft form Jay Parini’s One Matchless Time: A Life of William Faulkner (2004) and André Bleikasten’s William Faulkner: Une vie en romans (2007). The more I reflected on these formidable biographies, the more I warmed to the idea of connecting otherwise the life and the work, the work and the life. I called Alice, and she responded enthusiastically: the project was underway. I expanded the argument, Alice took it to a range of presses, and Oxford signed on. Suddenly, all I had to do was find the time—and figure out how—to bring to birth an idea that had begun as a gleam in the eye, but whose becoming was now a promised and contracted reality.

As often in my academic career, my home institution, Swarthmore College, provided me with the time: a full-year sabbatical leave (thanks to a Lang Fellowship) in 2007–2008. The wind in my sails, I began to conceptualize the book in a more sustained fashion. That is when—intent on (re)establishing for myself the story of Faulkner’s life—I began to incur indebtedness on a broader scale. I reread Joseph Blotner’s authorized biography, and I marveled (as I had not before) at the scope and scrupulousness of his work: the countless interviews conducted, the thousands of pages of unpublished and published work scrutinized, the contextual frames considered, in order to put Faulkner’s life into perspective. In his wake, a host of critical biographers—David Minter, Judith Wittenberg, Judith Sensibar, Frederic Karl, Richard Gray, Joel Williamson, James Watson, and among others, produced (prior to Parini and Bleikasten) compelling work seeking to interrelate Faulkner’s life and his creative output. Although I was undertaking a different kind of book, I benefited massively from their biographical labors. (My debt to Blotner is beyond accounting: he looms behind a third of my pages.) Finally, having come to grips as I could with previous biographies, I encountered (a few weeks before turning in my final manuscript) Sensibar’s just-published Faulkner and Love: The Women Who Shaped His Art (2009). Since she reads his life in terms that differ from my own, I have sought, in half a dozen notes, to engage her argument.

In between taking Alice Tasman’s phone call in 2002 and pondering Judith Sensibar’s argument in 2009, I have incurred a host of other debts. David Riggs (himself a biographer) generously read the biographical précis. Academic friends and colleagues—Robert Bell and Robert Roza—read each chapter, critically and sympathetically. John Matthews engaged the argument—as he has engaged all my work on Faulkner for the past twenty-five years—with an eye at once demanding and supportive. Jay Parini—familiar with both the territory I was pursuing and the challenges I would encounter—graciously perused the entire manuscript, and André Bleikasten attended to its argument as he could, while struggling with health issues. My twin brother Arnold gave me his unstinting attention, as he considered my take on materials he and I have been discussing together—and writing on—for decades.

Oxford University Press has supported this book in a number of ways. Shannon McLachlan who first saw and said yes to the project, Brendan O’Neill who labored to help me secure the photos in the book, Martha Ramsay who kept me on the right side of gender usage and even enjoined—at full page length!—several of my claims, Jessica Ryan who has given me the good of her response to my revisions: these Oxford professionals have made this a better book. Locating and getting permission to use the photos I wanted turned out to be a task of greater magnitude than anticipated. Fellow Faulknerian Robert Hamblin (head of the Center for Faulkner Studies at Southeast Missouri State University) both bailed me out and helped—along with Donald Kartiganer—to keep up my morale. Thanks also to Pamela Williamson, Curator of the Department of Archives and Special Collections of the University of Mississippi Libraries—home of the Coldfield Collection of Faulkner photos.

I close by dedicating this book to three people: Alice Tasman, whose belief in it galvanized me; my wife Penny, whose belief in me underwrites everything I have written; and André Bleikasten, peerless Faulknerian, in memoriam.

CONTENTS

Abbreviations

PROLOGUE “Cant Matter”

CHAPTER ONE Crisis and Childhood

CHAPTER TWO Untimely

CHAPTER THREE Dark Twins

CHAPTER FOUR In Search of Sanctuary

CHAPTER FIVE Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow

EPILOGUE “Must Matter”

Notes

Index

ABBREVIATIONS

FAULKNER EDITIONS CITED

AA

Absalom, Absalom! (1936), in Faulkner: Novels 1936–1940 (New York: Library of America, 1990).

AILD

As I Lay Dying (1930), in Faulkner: Novels 1930–1935 (New York: Library of America, 1985).

/>

ELM

Elmer (1925), in William Faulkner Manuscripts 1: Elmer and “A Portrait of Elmer,” with an introduction by Thomas L. McHaney (New York: Garland, 1987).

EPP

Early Prose and Poetry, ed. Carvel Collins (Boston: Little Brown, 1962).

ESPL

Essays, Speeches & Public Letters, ed. James B. Meriwether (New York: Random House, 1966).

FAB

A Fable (1954), in Faulkner: Novels 1942–1954 (New York: Library of America, 1994).

FD

Flags in the Dust, in Faulkner: Novels 1926–1929 (New York: Library of America, 2006).

FIU

Faulkner in the University, ed. Frederick L. Gwynn and Joseph Blotner (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1959).

GDM

Go Down, Moses (1942), in Faulkner: Novels 1942–1954 (New York: Library of America, 1994).

HAM

The Hamlet (1940), in Faulkner: Novels 1936–1940 (New York: Library of America, 1990).

HEL

Helen: A Courtship and Mississippi Poems, ed. Carvel Collins and Joseph Blotner (New Orleans: Tulane University Press, 1981).

ID

Intruder in the Dust (1948), in Faulkner: Novels 1942–1954 (New York: Library of America, 1994).

IIF

If I Forget Thee, Jerusalem (1939) (originally published as The Wild Palms), in Faulkner: Novels 1936–1940 (New York: Library of America, 1990).

LA

Light in August (1932), in Faulkner: Novels 1930–1935 (New York: Library of America, 1985).

LG

Lion in the Garden: Interviews with William Faulkner, 1926–1962, ed. James B. Meriwether and Michael Millgate (New York: Random House, 1968).

MAN

The Mansion (1959), in Faulkner: Novels 1957–1962 (New York: Library of America, 1999).

MF

The Marble Faun (1924), in The Marble Faun and A Green Bough (New York: Random House, 1965).

MOS

Mosquitoes (1927), in Faulkner: Novels 1926–1929 (New York: Library of America, 2006).

PYL

Pylon (1935), in Faulkner: Novels 1930–1935 (New York: Library of America, 1985).

RN

Requiem for a Nun (1951), in Faulkner: Novels 1942–1954 (New York: Library of America, 1994).

SAN

Sanctuary (1931), in Faulkner: Novels 1930–1935 (New York: Library of America, 1985).

SF

The Sound and the Fury (1929), in Novels 1926–1929 (New York: Library of America, 2006).

SL

Selected Letters of William Faulkner, ed. Joseph Blotner (New York: Random House, 1977).

SP

Soldiers’ Pay (1926), in Faulkner: Novels 1926–1929 (New York: Library of Amerca, 2006).

TN

The Town (1957), in Faulkner: Novels 1957–1962 (New York: Library of America, 1999).

OTHER FREQUENTLY CITED SOURCES

ALG

Meta Carpenter Wilde and Orin Borsten, A Loving Gentleman: The Love Story of William Faulkner and Meta Carpenter (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1976).

CH

John Bassett, William Faulkner: The Critical Heritage (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1975).

CNC

Ben Wasson, Count No ’Count: Flashbacks to Faulkner (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1983.

F

Joseph Blotner, Faulkner: A Biography: One-volume Edition (New York: Random House, 1984).

F2

Joseph Blotner, Faulkner: A Biography, 2 vols. (New York: Random House, 1974).

FCF

Malcolm Cowley, The Faulkner-Cowley File: Letters and Memories, 1944–1962 (New York: Viking Press, 1966).

FOM

Murry C. Falkner, The Falkners of Mississippi: A Memoir (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1967).

MBB

John Faulkner, My Brother Bill: An Affectionate Reminiscence (New York: Trident Press, 1963).

NOR

David Minter, ed. The Sound and the Fury (New York: Norton Critical Edition, 2nd ed., 1993).

OFA

Judith Sensibar, The Origins of Faulkner’s Art (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1984).

OMT

Jay Parini, One Matchless Time: A Life of William Faulkner (New York: Harper Collins, 2004).

TH

James G. Watson, Thinking of Home: William Faulkner’s Letters to His Mother and Father, 1918–1925 (New York: Norton, 1992).

WFSH

Joel Williamson, William Faulkner and Southern History (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993).

BECOMING FAULKNER

PROLOGUE

“CANT MATTER”

Because you make so little impression, you see. You get born and you try this and you dont know why only you keep on trying it and you are born at the same time with a lot of other people, all mixed up with them, like trying to, having to, move your arms and legs with strings only the same strings are hitched to all the other arms and legs … like five or six people all trying to make a rug on the same loom only each one wants to weave his own pattern into the rug; and it cant matter, you know that, or the Ones that set up the loom would have arranged things a little better.

—Absalom, Absalom!

What would a life look like if its inner sense conformed to this passage? How might someone else try to tell such a life? We assume that a life worth the telling involves a shaping force and weight, eventually cohering into something more than “so little impression.” But this passage insists on messiness and waste, on fruitless labor. It focuses on the failure of personal coherence to emerge in time. Others are there, alongside you from the beginning, and they get in your way. They desire as urgently as you do; their desire interferes with yours. The scene is mystifying. Each individual struggles to make something, but the larger cultural loom on which the individual “patterns” are plotted and pursued is defective, in ways that those striving below might guess at but cannot alter.1 All the actors become entangled like stringed puppets helplessly careening into each other’s space. The more they strive, the more inextricable the entanglement.

Becoming Faulkner: my title seems to invite us to consider the notion of “becoming”—of making something out of a life—in a more positive light. It promises the story of Faulkner’s becoming a writer and eventually a world-renowned artist. One anticipates a narrative of obstacles encountered and eventually dealt with. One expects Faulkner to achieve his becoming—to get his arms and legs (and mind and feelings and imagination and typewriter) into the clear. “Becoming” implies a gathered coherence, an achieved project not unlike Judith’s sought-after weaving, something gaining in sense and wholeness as it progresses. William Faulkner did become a great novelist (who would deny it?), I have become a writer about his achievement (my book is in your hands), and you may become a reader of my book. May—there’s the rub. Inasmuch as you are now where he and I once were—in the uncertainty of the present moment—you are in a position to recognize the concealed time-trick on which all claims of becoming are premised. You might not become my reader. In the present moment, this is something that has started but not yet concluded. You could put the book down. Move back a bit further in time, when this book was still to be written, and I might not have become its author. Move back further yet, to the present time of Faulkner, and Faulkner might not have become Faulkner. We know what any becoming looks like only because, after it has taken place, its force and weight are recognizable. Retrospection magically transforms the messy scene of ongoing present time into the congealed order it (later) appears always to have been headed for. But in the turbulent present moment—prior to an achieved becoming—there is … what?

In the vortex of the present moment there is frustration and confusion. Confined to that moment (which is where all human beings are confined, the time frame in which life itself is lived), one experiences—whenever the unanticipated arrives—bafflement rather than recognition. And on

e’s ability to cope with the unexpected is inseparable from the resources culturally bequeathed for coping. In Faulkner’s desiccated early-twentieth-century South—a place stubbornly facing backward—these resources were especially tenuous. Buffeted by events, one’s strenuous moves entangled with the countermoves of others, the Faulkner protagonist—like Judith Sutpen in that passage from Absalom!—feels certain of one thing: I cant matter. Judith experiences her life not as a project in the process of becoming but as an inexplicable derailment. Whatever undivulged purpose “the Ones that set up the loom” had in mind, it was hardly her own prospering. Judith goes to her grave not enlightened by the calm that follows a storm but marked by the storm that precedes any calm. Likewise, the trajectory of Faulkner “becoming Faulkner” took shape as a risk-filled project in ongoing time. Indeed, once his incapacity for progress ceased to torment him, his work began to lose its capacity to startle, awaken, disturb. The outrage of unpreparedness is the traumatic experience he learned to narrate—an outrage that, could he have avoided it in his own life, he might well have done so. And been freed perhaps from writing masterpieces.

B006JHRY9S EBOK

B006JHRY9S EBOK